Date: 23 Mar 2015

Source(s): United States Agency for International Development (USAID), United States of America – gov

By Colin Quinn

The first time I visited Pemba, Mozambique to begin a project that would help the port city adapt to climate change, I was not prepared for what I saw.

After a few days of severe rain last year, neighborhoods resembled wetlands, streets had turned into rivers, and a large piece of the main coastal road had fallen into the ocean. Residents of beachside villas were pumping water out of their living rooms. In Cariaco, a neighborhood built on a steep hill above the ocean, one man showed me a crack that had formed in his yard and under his house, an ominous sign.

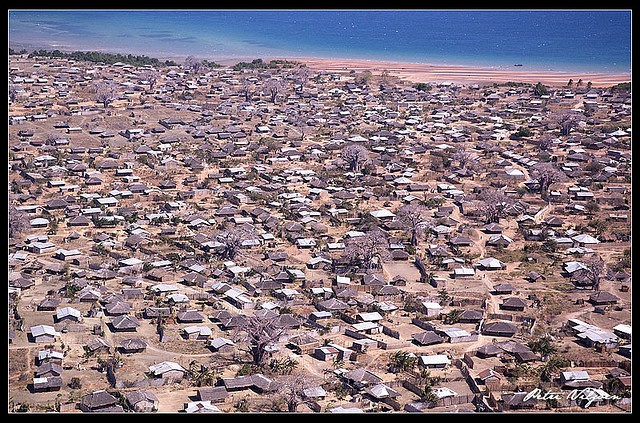

I had flown into Pemba in January 2014 to talk with the mayor about USAID’s Coastal City Adaptation Project. Pemba is a rapidly growing coastal city of about 150,000 people with a lot of economic potential due to the recent discovery of natural gas. But like most coastal cities in Mozambique, Pemba suffers from a lack of infrastructure — making natural disasters much more destructive. City officials and residents told us that the flooding I encountered had not been seen in Pemba for decades. The silver lining? We had clearly arrived at a fitting time to discuss climate change adaptation.

The future of Pemba, and of Mozambique, depends on its residents’ ability to adapt to climate change. Mozambique is among the African countries most vulnerable to climate change, with over 1,550 miles of coastline, more than half of its population living along the ocean, and cities that function as the nation’s economic hubs. Floods, droughts and tropical cyclones are all common. In places like Pemba, floods will likely become less predictable and more severe, magnified by sea level rise.

Now over a year into the project, our efforts have better prepared Pemba for climate change. Working with the local and central Mozambique government, we have developed an early warning and response system so that residents are better protected from severe floods. This system uses simple texting technology, on ‘smart’ and ‘dumb’ phones alike, to send alerts and request data that officials can use to respond to the hardest-hit areas first.

We have created maps to inform future city planning that show areas vulnerable to climate change. We have begun an ongoing, open dialogue with city officials, community leaders, local NGOs and other stakeholders about what it means to adapt to climate change. As a result, we are about to break ground on prototype climate-smart houses and rain catchment systems with local communities. We are also planning a project to stabilize dunes to help prevent flooding. We hope these activities will help Pemba prepare for an uncertain future.

I found myself back in Pemba in April 2014, two months after my first trip. The rains had returned–this time they were worse. A temporary camp was constructed for 66 families while they looked for places to rebuild their ruined homes. Food and drinking water were being distributed to those in need. A makeshift canal used to drain water from a neighborhood in January was now a full drainage canal covered by a permanent bridge. When I went back to Cariaco, the house over the crack in the ground was gone; it had been swept away in a landslide. There are no official numbers, but residents later told me 14 people had died in that area, with two people still missing.

We envision a city that is more resilient to extreme weather. When the rains return to Pemba in the future, our work will help families and communities be more prepared.

Through our capacity-building approach, better city planning will result in fewer people impacted, dunes will prevent floods caused by storm surge in soon-to-be-developed coastal zones, and families living in vulnerable areas will have built houses that are more suitable for extreme weather.

In the case of an emergency like last year’s flooding, the early warning response system we developed will alert people to danger so they can take necessary precautions. Over text, community leaders can inform emergency response officials about local risks and damages to ensure an appropriate response.

When I first arrived in Pemba I was not prepared for the magnitude of need I was going to see. After visiting, I know one thing for certain: We are working in the right place.

About the Author

Colin Quinn is a Climate Change Advisor and Natural Resources Officer with USAID’s mission in Mozambique.